A couple of months ago I had an article published in the Diplomat on the topic of how Trump’s national security team will shape his China policy.

I based my Diplomat article partly on a classification drawn up in by the European Council on Foreign Relations (EFCR) in 2022, identifying the different approaches to foreign policy within the Republican Party. The EFCR identified three camps within the party, which it called the primacists, the restrainers, and the prioritisers. This taxonomy gained widespread recognition, with publications like the Economist and the Lowy Institute picking it up.

According to this classification, the “primacists” are, essentially, those who would like to see the US preserve its leadership and military presence worldwide with the help of its allies. The “restrainers”, on the other hand, are what many would call isolationists. They think the US should focus on its domestic problems, and scale back its military commitments abroad.

Finally, the “prioritisers” are those who favour the projection of US power abroad, but feel that America simply doesn’t have the resources to focus on all theatres at once. Instead, they want to see the US scale back its engagement in Europe and the Middle East, while focusing its resources on the most pressing priority: confronting and containing China, which they see as a deep existential threat.1

The basic point of my article was that a majority of Trump’s picks for his national security and foreign policy posts seemed to fall into the prioritiser camp: they are China hawks who think the U.S. should focus its resources on containing China, while they seem uninterested in cultivating the United States’ traditional military alliances, particularly in Europe. Many of them are aligned with a growing body of opinion among Republicans that sees support for Ukraine’s war effort as an unnecessary burden for the US.

I included Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth, CIA director John Ratcliffe, US ambassador to the UN Elise Stefanik and Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem in this group. I noted that J.D. Vance also seemed to fall in this camp: he had claimed that the US is overstretching itself and cannot support both conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East and a potential war over Taiwan, and that it should put its focus squarely on China, while Europe should take responsibility for its own defence.

I also argued that Trump already seemed determined to impose tariffs on China, but on Taiwan and other points of geopolitical contention his position appeared murky and indecisive, and it was conceivable that his advisors could influence him to take a more assertive stance. He might be tempted to use the issue of Taiwan as a bargaining chip, but those around him were likely to tell him that this would run counter to US interests.

Two months have passed since I wrote my article, Trump has taken office, and his foreign policy has been even more bizzarre and concerning than most people were expecting. Some of his proposals, like taking over Greenland and the Panama Canal or turning Gaza into a new riviera, sound like jokes until you realise he is dead serious (or perhaps he isn’t?).

Trump’s wish to end the war in Ukraine on Russia’s terms is now plain for all to see. Is this part of a general shift towards isolationism and retrenchment from alliances in Europe and Asia, or is there a plan to appease Putin and then focus all of America’s resources away from Europe and onto its most powerful rival, China?

When it comes to China, Trump has predictably resumed his trade war, as he had made clear he would do (although it never really stopped even under Biden). He has also justified the threat of taking back control of the Panama Canal by saying it is “controlled by China”, suggesting that he does see Chinese influence around the world as a threat. In fact, while a Hong Kong company operates two of the five ports that service the canal, there is no evidence that any Chinese actor controls the canal.

Up to now Trump hasn’t made any eye-catching pronouncements regarding the situation in the Indo-Pacific. It is impossible to predict what his next move might be. His decision-making is unpredictable and fickle, and he is not beholden to any particular ideology or commitment to the international order; he sees everything in transactional terms. There have been, however, some timid signals that America’s long-term diplomatic support for Taiwan will continue.

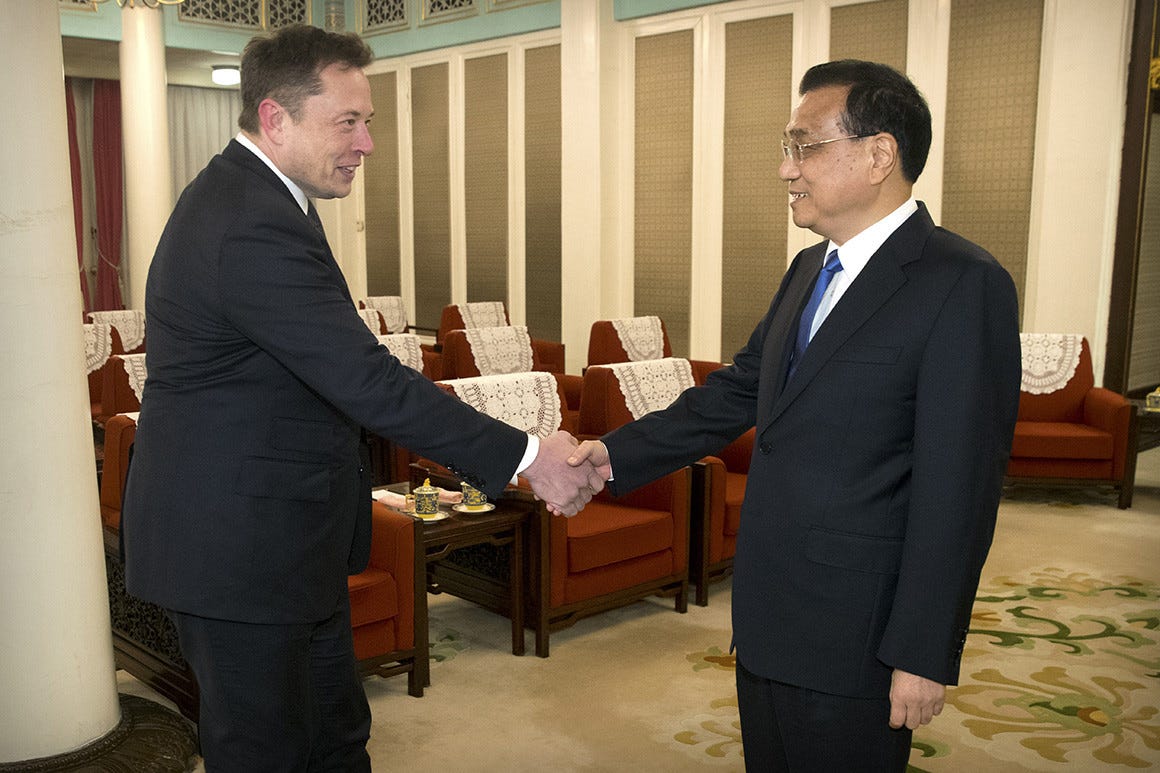

Further complicating the picture, Trump has come under the influence of Elon Musk, a self-interested man with deep ties to China. Tesla produces half the cars it sells worldwide in its Shanghai factory, which has received strong backing from the Chinese government. Li Keqiang even offered Musk a Chinese green card, which is very hard for foreigners to obtain; it’s unclear if he accepted it or not.

Unsurprisingly, Musk has a record of praising the Chinese political system and expressing support for China’s position on Taiwan. Apparently he is very concerned about the supposed lack of free speech in Europe, but this concern does not extend to China in the slightest.

All the same, within Trump’s administration the “prioritiser” line clearly still has a lot of adepts. Former Fox News presenter Pete Hegseth, now US Secretary of Defence, laid out this thinking quite openly at a defence summit in Brussels last Wednesday. Speaking to European defence ministers, he said “stark strategic realities prevent the United States of America from being primarily focused on the security of Europe”, and the US faces “a peer competitor in the Communist Chinese with the capability and intent to threaten our homeland and core national interests in the Indo-Pacific. The U.S. is prioritizing deterring war with China in the Pacific (…)”.

At the Honolulu Defense Forum, an annual gathering of American generals and national security elite which took place last week, the mood was rather similar. The Economist reports that Admiral Samuel Paparo, the head of America’s Indo-Pacific Command, told the attendees that “if you were to choose the world’s centre of gravity 100 years ago it would have been somewhere in east-central Europe. Today, it’s squarely in the Indo-Pacific.” He also sounded the alarm over the readiness of US troops in the region to confront China.

According to the magazine, some of the “China Hawks” in attendance at the forum expressed hopes that doing less in Europe would lead the US to do more in Asia, while others worried that if America lost credibility as an ally in Europe, it would lose it in Asia as well. The Economist itself points out that American arsenals are being depleted, and the US army’s munition shortage in Asia is caused at least in part by its support for Europe. Sending more air-defence systems to Ukraine means there are fewer left to protect US bases in the Pacific.

Trump comes across to much of the world as erratic, a buffoon, even a madman, but there is some method to his madness. There are certain beliefs he has held on to quite strongly over the years. One is that America’s trade relationship with China is unbalanced, and tariffs are the way to fix this. Another one is that America’s allies have been free-riding on America’s generosity, and they need to spend more for their own defence.

For the rest, all bets are open. Trump’s attitude towards China in general has been contradictory (and so have Chinese attitudes towards Trump, for whom many in China have an odd admiration). Unsurprisingly, he doesn’t seem to have a problem with the country’s authoritarianism. In fact, he has praised Xi’s leadership style on several occasions. Trump doesn’t particularly care for democracy, either abroad or at home, and he has no interest in leading a “coalition of democracies”. He does, however, care about other countries “taking America for a ride”, and he is convinced China has been doing this for years.

Whatever the plan, or the lack of one, one thing is certain: some of Trump’s moves, like pulling the US out of international bodies like WHO, exiting the Paris Agreement on climate change, and ending USAID programmes, are objectively going to undermine US leadership and standing in the world and give China a great chance to increase its own influence and prestige. “America first” is in many ways a gift to America’s rivals. Whether Trump realises this, and whether he cares, I have no idea.

Conservative commentator Tanner Greer, who used to live in Beijing, came up with his own version of the EFCR’s taxonomy to describe Republicans’ attitudes to China: he places them on a quadrant, with a fourth category (“internationalists”) added to the other three.