The Long Season: social realism in China's rust belt

A hit drama set in small-town Northeast China

I have just finished watching what has probably been China’s surprise hit of the year, 漫长的季节 (“The Long Season”).

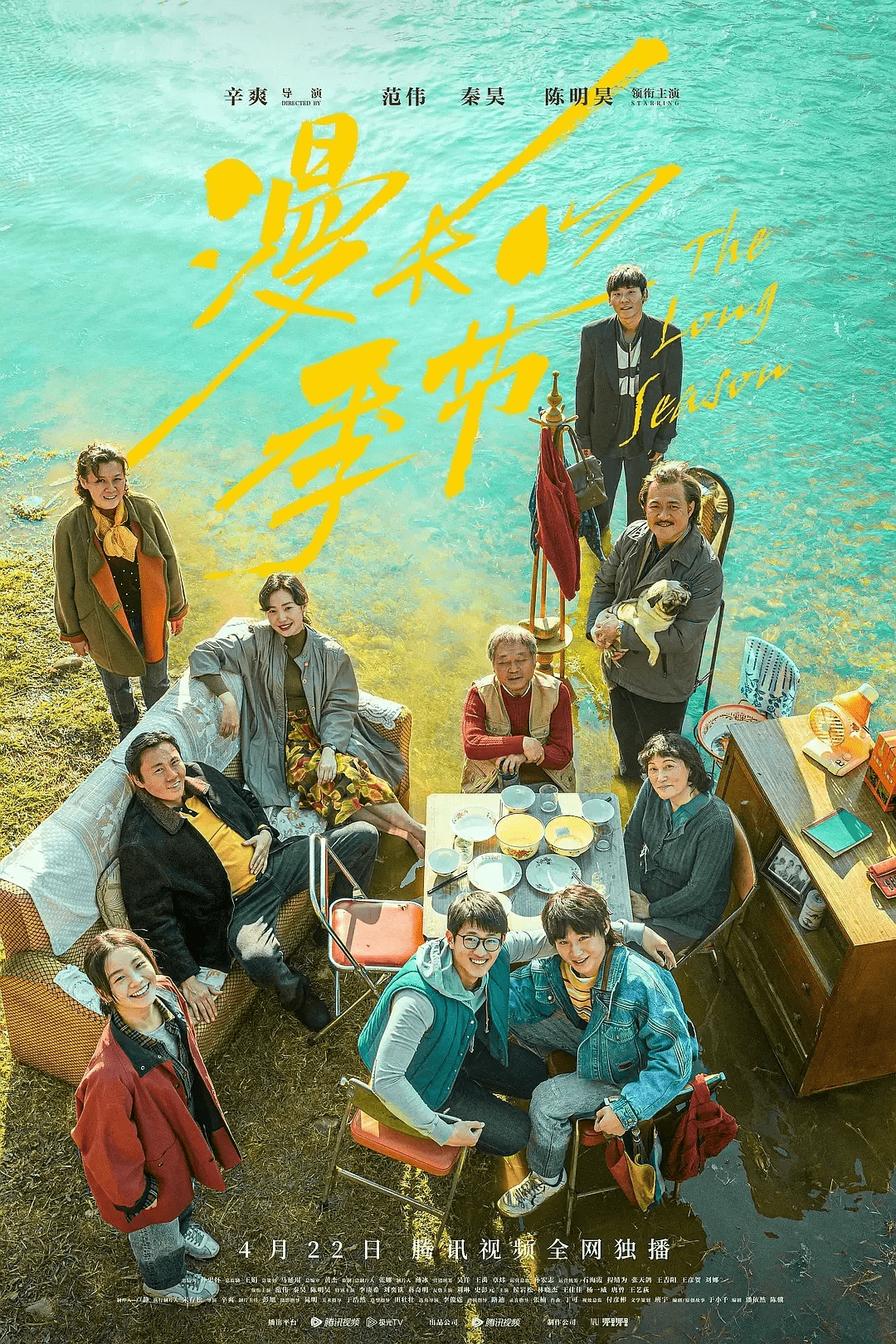

Just like most high-quality Chinese dramas, the Long Season was not broadcast on Chinese TV, but rather streamed on a video-streaming website, in this case Tencent Video. With this show, director Xin Shuang has pulled off a second success after the acclaimed 隐藏的角落 (the Bad Kids), another hit streaming drama from 2020. The two shows have a lot in common: 12 episodes, a realistic small town setting, and a gruesome murder that envelopes the lives of their characters.

The Long Season is set in a fictional small town in Northeast China called Hualin. The action jumps back and forth between two timelines, one set in 1998 and the other in 2016. In the 1998 timeline, the main character Wang Xiang is a middle-aged man with a wife and son, employed as a train driver for the local state-owned steel factory.

The factory has long been the linchpin of the town’s economy, and working there is a source of pride for Wang Xiang, but the times are changing, the enterprise is in dire straits and lots of workers are being laid off. Wang Xiang’s life is changed by an unresolved murder case, when parts of a dismembered corpse are discovered around the factory. The fallout eventually leads to him tragically losing his 20 year-old son Wang Yang, found dead in a river.

In the second timeline, set in 2016, we find that Wang Xiang is now driving a taxi to make a living. He is a lonely man in his sixties, whose only comfort is his adopted son, Wang Bei, who will soon move to Beijing for study. Due to an unforeseen series of events, Wang Xiang teams up with younger friend Gong Biao and former police inspector Ma Desheng to hunt down a scammer with a fake licence plate, and ends up finding a connection with the old murder case that still haunts him.

The Long Season certainly has artistic worth. The story is compelling, and the acting is top-notch and highly realistic, quite unlike the stilted and clichéd style often seen in Chinese TV shows. The shift between the 1998 and 2016 timelines is extremely well executed. The actors are the same, but they really do look two decades older. It isn’t just about their make up; the way they carry themselves also gives you a convincing impression of people who have aged and have been weighed down by life’s troubles.

The show’s soundtrack, based mostly on underground Chinese rock music, is very good as well and has received widespread acclaim. This is not too surprising, when you consider that the director used to be a guitarist in a famous punk band. Especially for those interested in Chinese politics and society, on the other hand, it is the show’s depiction of the social problems of a small town in Northeast China at the turn of the century that is most interesting.

China has changed tremendously over the past 25 years, and the atmosphere of the time is carefully reconstructed: the streets are still grey and grim, and there are few of the colourful shops and department stores you would see today. Most people still get around by bicycle, while the young queue up in front of little cinemas showing Titanic dubbed in Chinese. Below the surface a generational gap has opened up in society, best exemplified by the relationship between Wang Xiang and his son.

It is important to understand the historical context. In the late 90s the Chinese economy was being reformed to make it more efficient and less state-centred: a “socialist market economy” in the definition coined by Jiang Zemin, which will seem hilariously contradictory to many. The authorities popularised the slogan 抓大放小 (grasping the large and letting the small go), meaning that the government would keep control of the larger state-owned enterprises, but allow local governments to restructure, privatise or disband the smaller ones.

All of a sudden, millions of workers across China were laid off from their jobs in state-owned enterprises. It is impossible to overstate how disruptive this was for them. These jobs represented more than just a source of income. Such enterprises offered their employees cradle-to-grave welfare and a sense of identity. Workers usually lived in compounds attached to their factory or offices, where everyone belonged to the same “work unit”. There would also be schools and medical centres for the workers and their families. People could spend their entire lives ensconced in such communities, and live like the outside world did not exist.

Northeast China (a region of which The Long Season’s director is a native) was hit particularly hard in this transition. Under Chairman Mao it had become one of China’s most industrialised regions, but it was not well-placed to benefit from the new market economy. There was little fallback for laid-off workers. English-language media today sometimes refers to the region as China’s “rust belt”, not without reason.

The Long Season’s main character Wang Xiang is a product of the planned economy. His father worked in the same state-owned steel factory he does, and he has spent all of his life there. He lives in a simple apartment and gets around by bicycle, but as a driver of the trains that carry the factory’s steel, “Master Wang” (王师傅) enjoys the respect of his peers.

And yet it is clear that the closed and regulated world of the state-run factory may not last much longer. Mass lay offs are on the horizon, and the workers nervously wonder who will be on the next 下岗名单, the list of those to be made redundant. Occasionally they express their frustration with violent agitations, furious and bewildered that their jobs for life are no longer for life. Some of the local youngsters, who find they are not getting hired anymore, turn to nihilism and petty crime.

Wang Xiang’s son Wang Yang has a different outlook from his father. He has failed the college entrance exams, and his father wants to see if he can secure him a job at the factory, but Wang Yang is uninterested. Perhaps he senses that the factory is already in a crisis, but he is also unimpressed by his father’s narrow outlook on life.

As Wang Yang complains one day to his crush Shen Mo, the train tracks his father drives on every day can take you all the way to Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, but he never went to any of those places, because he thinks of Hualin and the steel factory as his entire world. Wang Yang doesn’t want to live the life his father did; he wants to see the wider world.

Some claim that The Long Season’s popularity in China is a reflection of the longing for the stability of the past, now that the dream of overnight wealth in the private economy no longer seems as realistic as it used to. And yet the show does not romanticise life in the state-owned enterprise as some simple but happy socialist past. There is plenty of corruption and meanness, starting with the director who is misappropriating public funds (in the end he is put under investigation, but perhaps this is the show’s way of remaining within politically acceptable standards).

The factory has its own internal security, independent of state police, run by the villainous Xing Jianchun, who tries to supplement his income by illegally reselling the factory’s assets. When Wang Xiang finds out and refuses to be bribed into allowing the stolen goods on his trains, Jiangchun vows revenge.

He eventually gets his chance when he lures Wang Xiang’s unsuspecting son into the accounting office, telling him his father is waiting for him there. He then locks him inside and calls his subordinates in the security department, who believe him to be a thief. The security personnel then parade Wang Yang through the streets as a thief, something that was still common and acceptable in China at the time (and in some contexts still is today).

Wang Xiang rushes to the scene, but he soon realises that his son’s word won’t be believed against the powerful security boss. In the end he is forced to promise Jianchun that he will facilitate his illegal trade in order to prevent him reporting his son to the police, something which would leave a lifelong mark on his record.

As imperfect as it was, the world of the state-run “work unit” offered its inhabitants a structured environment in which their livelihood was secure. In the show’s 2016 timeline, things have changed. The town looks more prosperous, although it is still essentially a drab place, but the main characters all have an air of despondency about them.

Gong Biao, Wang Xiang’s younger friend, has changed completely. In 1998 he is a good-looking and educated young man who works in the factory’s administrative department and has high hopes for the future. He falls in love with nurse Huang Liru, a cousin of Wang Xiang’s wife, and the train driver helps arrange the marriage, becoming a lifelong friend and ally.

In 2016, he has turned into a bitter middle-aged man who also drives a taxi for a living and is estranged from Liru, who illegally runs a beauty centre from her own flat while waiting for the permits to legally start the business. The lack of opportunity, boredom and frustration of life in small-town Northeast China are taking their toll on the couple.

Xing Jianchun, the steel factory’s security boss, also makes an appearance in the 2016 timeline. Now that he has left the factory he has become a truly pathetic figure, forced to sell fake licence plates to supplement his meagre pension so he can make enough money to treat his uremia.

This is another thing that makes The Long Season worth watching: it doesn’t sugarcoat the reality of life for the 老百姓, the common folk. While it steers clear of any political red lines, it shows you a side of life that Chinese TV shows, too busy trying to spread 正能量 (“positive energy”, as the slogan goes), generally refrain from showing.

In the show’s 1998 timeline one of the characters, a waitress at the town’s karaoke parlour, is eating dinner with her friend Shen Mo when she spills out her life story. When she was growing up, she says, her mother used to sell 煎粉 (a regional snack based on potato starch cubes) at a roadside stall. After getting off from school, she would also help out at the stall.

Her mother lived frugally, so she could pay for her daughter’s tuition fees. She was so frugal that she bought the cheapest type of gas tank for her stall. One day the gas tank exploded, and her mother was left with burns all over her body. She couldn’t afford the hospital bills, so she killed herself by drinking pesticide.

This bleak story is only included in passing, and I don’t think it’s even meant as a social critique, but it is a realistic example of the sort of tragedy that could befall the poor if they were unlucky, at a time when safety nets where close to zero.

Things have improved since the 90s in this respect, and healthcare and education in China are now subsidised to a much higher degree than they used to be, although they still aren’t universally free. A story that bleak would probably be less realistic today. But watching a drama like this one is still a good antidote to the myths about China that are widely believed in certain circles.